Serif vs. Sans: Typography Basics And Loads Of Free Fonts (Infographic)

You are really telling me, you never heard of Urban Fonts before? Well, considered how large the web is, this might be true and not a matter of faulty memory. The good news is: you can always get to know them now. They have published a useful infographic and still offer around 8.000 freeware fonts. So go there for more than one reason...

Urban Fonts Provides Thousands Of Free Fonts

I personally know Urban Fonts since the beginning of time. We were swimming the primeval soup together. I became a man, they became a type foundry. Caprice of fate.

Seriously. I first noticed Urban Fonts about six years ago. Being still around on the fast moving internet does mean something. Obviously, Urban Fonts did things right. Still, most of the portfolio on Urban Fonts are freeware fonts in formats for Mac and Windows, as there are TTF or OTF. License files are part of every download. So make sure the font you are going to use carries the proper license to let you.

Besides fonts from the freeware, premium fonts are available, too. Also there are fonts who demand backlinks, donations or any other token of appreciation the respective creators demand for. As I said, each font is equipped with a text-file to inform you, so you won't find yourself dashed against the wall in the wrong moment.

A nice feature for users looking for letter-sets other than English is the possibility to type your own text on the preview page of each font. That way you can check if a given font is worth to be taken into consideration very easily and reliably.

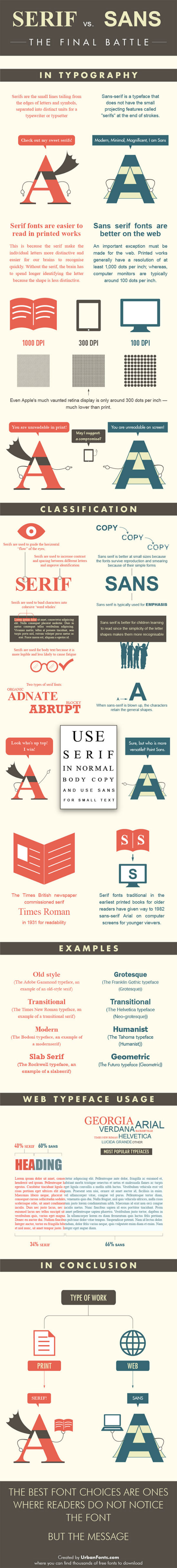

Serif vs. Sans: The Final Battle In Typography

Besides offering a plethora of free and non-free fonts, Urban Fonts runs a regularly updated blog, stuffed with interesting topics from the world of typography. You should consider subscribing to their RSS feed, if you are into typographical content.

Just this past week the UF team published an infographics on the differences between fonts with serifs and those without. Titled Serif vs. Sans they put together the most important distinguishing characteristics of the two families.

They don't limit the information to visible distinguishing marks, where obviously fonts with serifs carry - well - serifs, those little tailing lines around the edges of a letter. But they also explain the historical background as to how and why serif and sans fonts evolved.

If you are professional designer it will probably not be new to you, that still, serif-usage is advised for print, while sans-usage is advisable for web use-cases. So it is unsurprising that font usage on the web is 60% sans and 40% serif in headings, and even 66% sans in paragraph text, with only a share of 34% of serif.

Foremost because of the relatively low resolutions we still have to face as far as digital devices are concerned, sans is a better choice there. Serif fonts tend to brake and look brittle on resolutions lower than print. Even the coming hiDPI devices will have to go a long way to really be able to compete with a printed page of a book.

Put this infographic in your collection of infographics - I know you have one, if not, change that - to have it at hand when you next need it. As always, clicking the following image takes you to the source:

(Source: Urban Fonts Blog)

Related Links:

- Homepage | Urban Fonts

- Browse Favorite Free Fonts | urbanfonts.com

- Serif vs Sans: The Final Battle | Urban Fonts Blog

Nice infographic about SANS vs SERIF, thanks for sharing.

Personally I love slab serif (brix slab, museo slab..) and sans like proxima nova, source sans and open sans.

print with 1000 dpi? come on…

I’m a graphic designer and everyone uses 300-dpi images for offset printing. The only time I’ve used a higher dpi was when I worked on Betty Crocker Cookbooks, which used 1200-dpi, but they were ultra critical. For 99% of the jobs you’ll do, 300-dpi is more than adequate.

I believe the 1,000 dpi argument in print was referring to type more than images. Everything in print gets ripped/rasterized in the end to usually 1,200 dpi, depending on the printer or instructions included within the source file(s). Although, most fonts today have vector outlines, text is ripped like everything else in print. Compare printed 300 dpi text to 1,200 dpi and see a noticeable difference in clarity between them. Much like comparing the first generation iPad to the 4th generation, there is an obvious distinction in sharpness. In a nutshell, the difference between digital and print is that on screen, vector remains, in print, vector gets rasterized.

I actually use daFont as my source of typefaces. I’ve just checked Urban Fonts and I see that it has a decent collection too, so I’ll guess I’ll hang out there and explore a bit. That’s a great and informative infographic by the way and I love the end message. How the message is presented always matter more than its design. :)

300 DPI is the resolution of the first laser printers. I don’t recall anyone ever claiming that you shouldn’t use serif fonts with an Apple LaserWriter.

There is a difference between pixels and dots. A pixel in general will need many dots to be represented in most printing processes. The term DPI is really an unfortunate and inaccurate choice (vs. PPI) for describing display resolutions. 300 PPI do allow for way more fine-grained display compared to 300 DPI. Screens do not need 1200 PPI if printers do not need, say, 4800 DPI.