Mervyn Peake: An Illustrator and Writer Ahead of his Time

*all pictures by Mervyn Peake unless stated.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="500"] (Mervyn's Peake's self portrait) What do I care for the symbolism of it all? What do I care if the castle's heart is sound or not? I don't want to be sound anyway! Anybody can be sound if they're always doing what they're told. I want to live! Can't you see? Oh, can't you see? I want to be myself, and become what I make myself, a person, a real live person and not a symbol anymore. (from Gormenghast.)[/caption]

If as Aristotle stated "the aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance then Mervyn Peake's illustrated Gormenghast trilogy is one of the 20th century's greatest examples. Re-imagining the feudalistic China of his youth inside the dark maze like corridors of Gormenghast castle, he creates an atmosphere all ready ripe for the violence and corruption that unfolds in his first two books. While Titus Groan, the trilogy's main character, escapes this stifling existence in the final installment, he can never forget it. Like with Mervyn Peake's own experiences as a war artist the madness and death he witnessed shadows his each and every one of his thoughts and actions.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="500"]

(Mervyn's Peake's self portrait) What do I care for the symbolism of it all? What do I care if the castle's heart is sound or not? I don't want to be sound anyway! Anybody can be sound if they're always doing what they're told. I want to live! Can't you see? Oh, can't you see? I want to be myself, and become what I make myself, a person, a real live person and not a symbol anymore. (from Gormenghast.)[/caption]

If as Aristotle stated "the aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance then Mervyn Peake's illustrated Gormenghast trilogy is one of the 20th century's greatest examples. Re-imagining the feudalistic China of his youth inside the dark maze like corridors of Gormenghast castle, he creates an atmosphere all ready ripe for the violence and corruption that unfolds in his first two books. While Titus Groan, the trilogy's main character, escapes this stifling existence in the final installment, he can never forget it. Like with Mervyn Peake's own experiences as a war artist the madness and death he witnessed shadows his each and every one of his thoughts and actions.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="500"] He... jogged the gray mare to a trot and then into a canter, and finally with a moonlit wilderness before him, to a gallop. And so, exulting... with his eyes fixed excitedly upon the blurred horizon – and the battering of the hoof beats in his ears, Titus rode out of his world.[/caption]

Yet while Tientsin was the China he knew and loved it was his father's descriptions of the fortified Chinese capital of Beijing (he kept a detailed journal of all his travels through China) that formed the basis of the feudalistic society he depicts in the world of Gormenghast.

He... jogged the gray mare to a trot and then into a canter, and finally with a moonlit wilderness before him, to a gallop. And so, exulting... with his eyes fixed excitedly upon the blurred horizon – and the battering of the hoof beats in his ears, Titus rode out of his world.[/caption]

Yet while Tientsin was the China he knew and loved it was his father's descriptions of the fortified Chinese capital of Beijing (he kept a detailed journal of all his travels through China) that formed the basis of the feudalistic society he depicts in the world of Gormenghast.

Very little communication passed between the denizens of these outer quarters and those who lived within the walls, save when, on the first June morning of each year, the entire population of the clay dwellings had sanction to enter the Ground in order to display the wooden carvings on which they had been working during the year. These carvings blazoned in strange color, were generally of animals or figures and were treated in a highly stylized manner peculiar to themselves. (from Titus Groan)When his father first visited the city at the turn of the 20th century, Beijing was divided by walls into four parts – the inner city, the outer city, the imperial city and the forbidden city. Which part of the city a person lived in depended both of their status or on their ethnicity. The Han Chinese – a more than 90% majority - lived in the outer city - or the areas outside the city walls - while the recently dethroned Ming Chinese lived in the inner city. The Imperial city and the Forbidden city was reserved for those connected with the ruling Quing dynasty. After the Xianhai revolution in 1911, and Emperor Puyi's subsequent abdication, Peake's father was one of the first foreigners allowed access to the palace's outer courts. What he saw is immortalized in Gormenghast's Hall of Bright Carvings. [caption id="" align="alignnone" width="500"]

Standing immobile these vivid objects, with their fantastic shadows on the wall behind them shifting and elongating hour by hour with the sun's rotation, exuded a kind of darkness for all their color. The air between them was turgid with contempt and jealousy. (from Titus Groan. Picture by Ian Morris)[/caption]

In 1922 the 12 year-old Mervyn Peake stepped onto English soil for only the second time. It was a different universe. Cars had replaced mules, gray Christian churches had replaced the gold Buddhist temples and simple handshakes had replaced the complex rules and rituals of the Chinese greetings.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="500"]

Standing immobile these vivid objects, with their fantastic shadows on the wall behind them shifting and elongating hour by hour with the sun's rotation, exuded a kind of darkness for all their color. The air between them was turgid with contempt and jealousy. (from Titus Groan. Picture by Ian Morris)[/caption]

In 1922 the 12 year-old Mervyn Peake stepped onto English soil for only the second time. It was a different universe. Cars had replaced mules, gray Christian churches had replaced the gold Buddhist temples and simple handshakes had replaced the complex rules and rituals of the Chinese greetings.

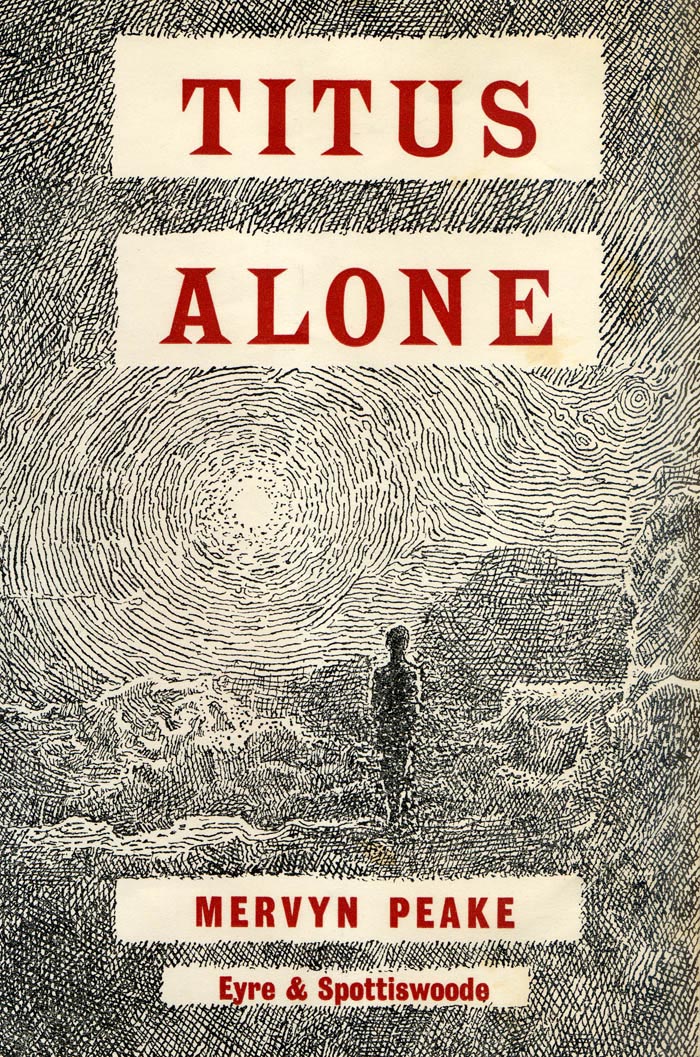

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="500"] As he stared at the high slopes of the city... His responses were no longer clear and simple, for he had been through much since he had escaped from Ritual, and he was no longer child or youth, but by reason of his knowledge of tragedy, violence and the sense of perfidy, he was far more than these, though less than man. (from Titus Alone)[/caption]

Peake was always going to find it difficult to settle in England and it was no surprise that, that at the age of 23, he left the mainland to join an art colony on the British Isle of Sark. With only 300 people – most of them fisherman – living on its 5km2 of granite rock, Peake could again return the outsider's life he had so enjoyed in China.

Living on Sark gave him the freedom create such works of art as this oil painting of a Sark fisherman.

As he stared at the high slopes of the city... His responses were no longer clear and simple, for he had been through much since he had escaped from Ritual, and he was no longer child or youth, but by reason of his knowledge of tragedy, violence and the sense of perfidy, he was far more than these, though less than man. (from Titus Alone)[/caption]

Peake was always going to find it difficult to settle in England and it was no surprise that, that at the age of 23, he left the mainland to join an art colony on the British Isle of Sark. With only 300 people – most of them fisherman – living on its 5km2 of granite rock, Peake could again return the outsider's life he had so enjoyed in China.

Living on Sark gave him the freedom create such works of art as this oil painting of a Sark fisherman.

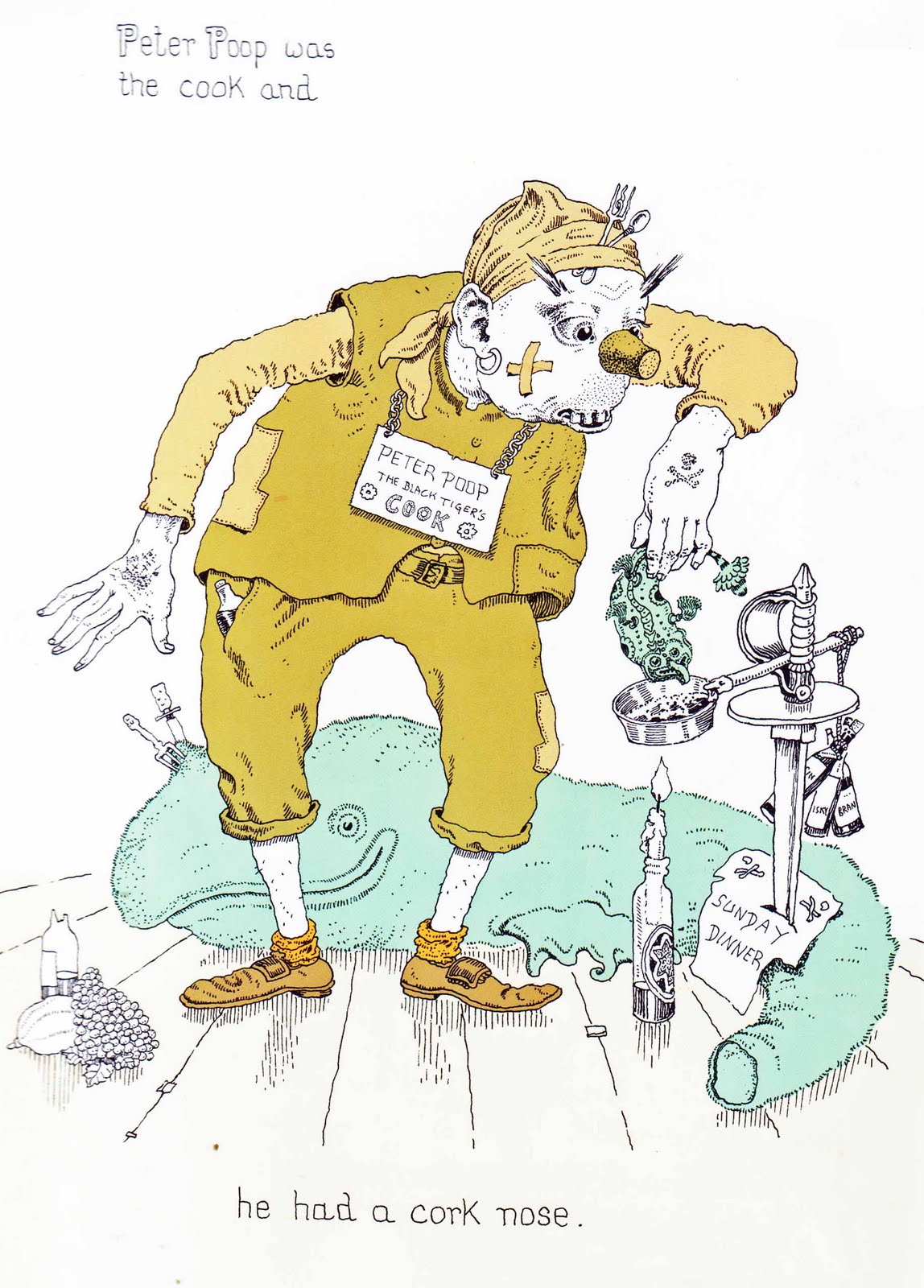

Writing and illustrating the children's book Captain Slaughterboard Drops Anchor (1939)

Writing and illustrating the children's book Captain Slaughterboard Drops Anchor (1939)

and ultimately develop a following that would lead to the publishing company Chatton and Windus commissioning him to illustrate such classics as Lewis Carroll's Hunting of the Snark(1941)

and ultimately develop a following that would lead to the publishing company Chatton and Windus commissioning him to illustrate such classics as Lewis Carroll's Hunting of the Snark(1941)

and S. T Coleridge's Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1943)

and S. T Coleridge's Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1943)

Yet while these pictures prove his style was already very intense and self-expressive, it would be his work as a war artist at the Belsen concentration in the aftermath of the Second World War that would give it that dark grotesque edge we see on the pages of each of his Gormenghast novels. One has to remember he wasn't shooting a photograph of a dead or dying person and then moving onto the next one. He was sitting down, observing them, sketching out draft after draft before finally finding the best way to depict and represent their suffering. You only have to look at the following illustration, descriptions role of the following characters of Gormenghast to understand the effect it had on his imagination.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="500"]

Yet while these pictures prove his style was already very intense and self-expressive, it would be his work as a war artist at the Belsen concentration in the aftermath of the Second World War that would give it that dark grotesque edge we see on the pages of each of his Gormenghast novels. One has to remember he wasn't shooting a photograph of a dead or dying person and then moving onto the next one. He was sitting down, observing them, sketching out draft after draft before finally finding the best way to depict and represent their suffering. You only have to look at the following illustration, descriptions role of the following characters of Gormenghast to understand the effect it had on his imagination.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="500"] Their apprehension had grown so dark, their speculation so fantastic that when they crept to the second door and peered into the apartment below and they saw in the center of the great carpet that filled the room the two skeletons lying side by side in their fast decaying dresses of imperial purple, their pulse beat no faster. Their emotions had been over-strained and had gone limp. But their brains raced.[/caption]

Their apprehension had grown so dark, their speculation so fantastic that when they crept to the second door and peered into the apartment below and they saw in the center of the great carpet that filled the room the two skeletons lying side by side in their fast decaying dresses of imperial purple, their pulse beat no faster. Their emotions had been over-strained and had gone limp. But their brains raced.[/caption]

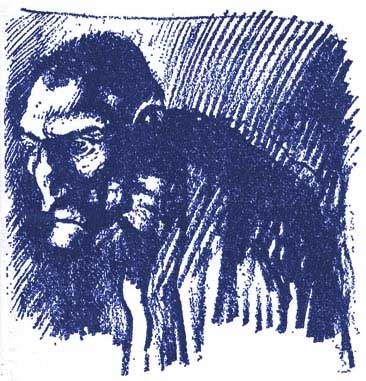

Flay

Flay, Lord Sulpchrave's, loyal servant, is so bony his knees creak as walks the castle's corridors. At the end of the first book the countess banishes him for throwing one of her pet cats at the evil Steerpike, but that is not the end of his character. In the second book he comes back to help save Gormenghast from Steerpike's evil schemes. [caption id="" align="alignnone" width="500"] It did not look as though such a bony face as his could give normal utterance, but rather that instead of sounds, something more brittle, more ancient, something dryer would emerge, something perhaps more in the nature of a splinter or fragment of stone. Nevertheless, the harsh lips parted. ‘It's me,’ he said, and took a step forward into the room. (from Titus Groan)[/caption]

It did not look as though such a bony face as his could give normal utterance, but rather that instead of sounds, something more brittle, more ancient, something dryer would emerge, something perhaps more in the nature of a splinter or fragment of stone. Nevertheless, the harsh lips parted. ‘It's me,’ he said, and took a step forward into the room. (from Titus Groan)[/caption]

Fuschia

Fuschia is Lord Sulphrave's daughter. After witnessing her father's decline into madness and falling for murderous Steerpike's charms, she jump off her window sill and into the castle moat. [caption id="" align="alignnone" width="500"] As his lord stared at the door another figure appeared, a girl of about fifteen with long, rather wild black hair. She was gauche in movement and in a sense, ugly of face, but with how small a twist might she not suddenly have become beautiful. (from Titus Groan)[/caption]

As his lord stared at the door another figure appeared, a girl of about fifteen with long, rather wild black hair. She was gauche in movement and in a sense, ugly of face, but with how small a twist might she not suddenly have become beautiful. (from Titus Groan)[/caption]

Titus Groan

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="448"] Titus is Seven. His confines, Gormenghast. Suckled on shadows; weaned as it were on webs of ritual for his ears, echoes, for his eyes a labyrinth of stone yet within his body something other – other than this umbrageous legacy. For first and ever foremost he was child. (from Gormenghast)[/caption]

Titus is Seven. His confines, Gormenghast. Suckled on shadows; weaned as it were on webs of ritual for his ears, echoes, for his eyes a labyrinth of stone yet within his body something other – other than this umbrageous legacy. For first and ever foremost he was child. (from Gormenghast)[/caption]

Steerpike

Charming, yet evil, Steerpike's determinate rise from kitchen boy to ruler of the castle leads to the deaths of Lord Selphcrave, Sourdust, Barquentine and Fuschia and the twins. Titus Groan eventually stabs him to death after an epic chase though the castle. [caption id="" align="alignnone" width="500"] High-shouldered to a degree little short of malformation, slender and adroit of limb and frame, his eyes close-set and the color of dried blood, he is climbing the spiral staircase of the soul of Gormenghast, bound for some pinnacle of the itching fancy - some wild, invulnerable eerie best known to himself; where he can watch the world spread out below him, and shake exultantly his clotted wings. (from Gormenghast)[/caption]

Mervyn Peake had planned to write a series of Gormenghast books. Unfortunately, while writing Titus Alone, he was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. By the late 50s he could only draw or write with the help of his wife. By the 60s he couldn't even hold a pencil. On November 17th 1968 – unaware of his books' growing cult status – Mervyn Peake passed away in a care home run by his brother in law, leaving behind a wife, three children and one of the most influential fantasy trilogies ever written.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="500"]

High-shouldered to a degree little short of malformation, slender and adroit of limb and frame, his eyes close-set and the color of dried blood, he is climbing the spiral staircase of the soul of Gormenghast, bound for some pinnacle of the itching fancy - some wild, invulnerable eerie best known to himself; where he can watch the world spread out below him, and shake exultantly his clotted wings. (from Gormenghast)[/caption]

Mervyn Peake had planned to write a series of Gormenghast books. Unfortunately, while writing Titus Alone, he was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. By the late 50s he could only draw or write with the help of his wife. By the 60s he couldn't even hold a pencil. On November 17th 1968 – unaware of his books' growing cult status – Mervyn Peake passed away in a care home run by his brother in law, leaving behind a wife, three children and one of the most influential fantasy trilogies ever written.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="500"] There was a library and it is ashes. Let its long length assemble. Than its stone walls its paper walls are thicker; armored with learning, with philosophy, with poetry that drifts or dances clamped though it is in midnight. Shielded with flax and calfskin and a cold weight of ink, there broods the ghost of Sepulchrave, the melancholy Earl, seventy-sixth lord of half-light.[/caption]

A self portrait of Mervyn Peake.

There was a library and it is ashes. Let its long length assemble. Than its stone walls its paper walls are thicker; armored with learning, with philosophy, with poetry that drifts or dances clamped though it is in midnight. Shielded with flax and calfskin and a cold weight of ink, there broods the ghost of Sepulchrave, the melancholy Earl, seventy-sixth lord of half-light.[/caption]

A self portrait of Mervyn Peake.

Great project

Amazing write-up, Simon! Peake, indeed, was a genius.

In the second year of my Graduation, I had prepared a term paper on “Mr. Pye” by Mervyn Peake. Peake was not part of our curriculum, and I had insisted on taking up this topic simply because I enjoyed going through his works. Your article reminded of the great time I had when I was studying Mr. Pye. :-)